Conservation Assured Tiger Standards

CA|TS provides an opportunity for individual tiger conservation areas or networks of areas to demonstrate their commitment to, and success in, protecting tigers. It is a voluntary, independent scheme for any area involved in tiger conservation.

Conservation Assured

Tiger standard

The first species-specific CA standards established was for the tiger (Panthera tigris). Few tiger conservation areas are truly effective refuges for tigers and this has contributed to a catastrophic decline in their numbers. Tigers have already disappeared from several protected areas where they were until recently regarded as secure. Ensuring a long-term an sustainable future for this iconic species cannot be achieved without a significant increase in the effectiveness of the tiger conservation areas across tiger range countries. The Conservation Assured | Tiger Standards (CA|TS) scheme provides an incentive to those responsible for tiger conservation areas in the 13 tiger range countries to improve the effectiveness of management. The approach is based on long-term experience of both environmental certification schemes (e.g. the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC)) and protected area management effectiveness assessments (e.g. the IUCN World Commission on Protected Areas (WCPA) Management Effectiveness Framework and associated systems) as well as a wide range of conservation management tools and expert knowledge.

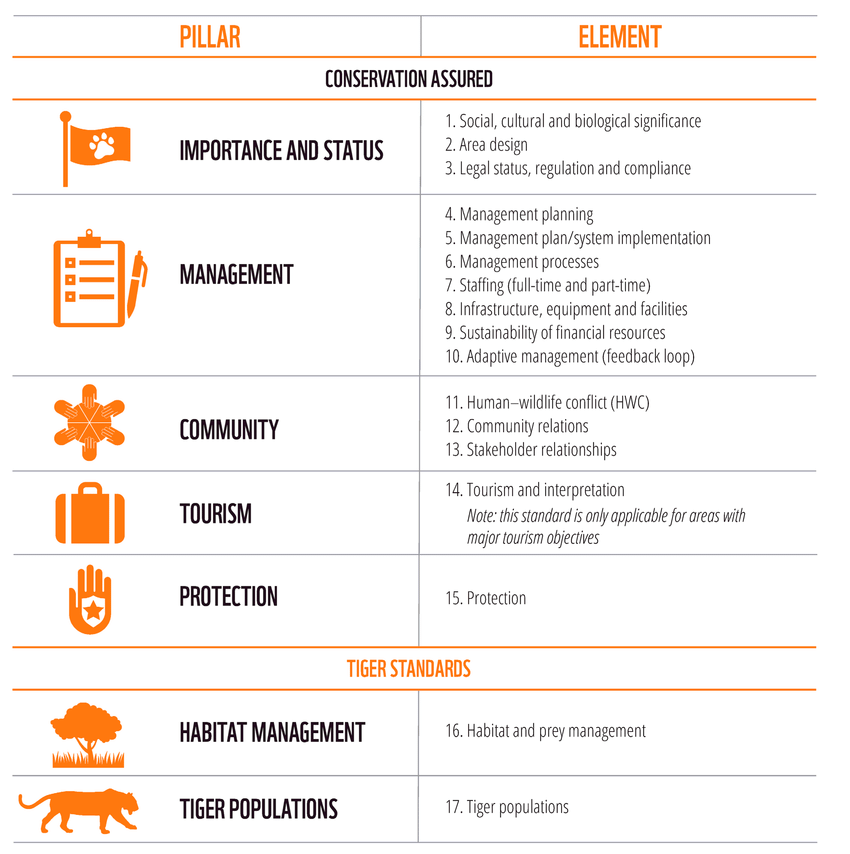

CA|TS is a set of 17 minimum elements with associated standards and criteria for effective management of tiger conservation areas. It is not a new management effectiveness system or a ranking of tiger conservation areas; but rather provides the means to tell if a particular area attains the best practice standards needed to conserve tigers. Tiger conservation areas taking part in the system are recorded as either Registered (but standard not yet attained) or as Approved (achieving the standards as verified through an auditing and independent review process); excellence is expressed by highlighting specific best practices. Whether tiger conservation areas meet the criteria is based on a process which starts with self-assessment, progresses through a system of national audit and is finally approved by an international executive committee, which ensures equivalence across tiger range countries.

CA|TS has been extensively field-tested and subjected to expert peer review (see acknowledgements for details). This second version of the manual was developed after a public consultation in 2017 and reflects the CA|TS Business Plan published in 2018 (CA|TS, 2018). Updated versions will continue to be produced as our knowledge and systems progress.

Why do we need standards to secure tiger numbers?

The rapid decline in populations of wild tigers continued despite major investment in their conservation (Damania et al, 2008). This failure forced a rethink in tiger conservation strategies towards a proposal that effort should be

focused on securing tiger populations in a number of key protected areas (GTI, 2011). This proposal was broadly supported at the International Tiger Forum in St Petersburg in 2010, within the broader framework of tiger landscape conservation.

A decision to focus on tigers in conservation areas narrows the priorities of conservation investment to policies and actions that maximize the effectiveness of these areas in securing wild tiger populations. This effectiveness tends to be assumed rather than proven in conservation literature; the small number of detailed studies suggests that this assumption is sometimes over-optimistic (e.g. Craigie et al, 2010). Protected areas are a good strategy for retaining vegetation cover; however their role in protecting animal species is more equivocal and dependent largely on the quality and focus of management. Many studies show that large animal species can continue to decline within protected areas, particularly due to bushmeat hunting or poaching of animals for traditional medicines, trophies, the pet trade and other illegal outlets. The loss of tigers from many protected areas is an indicator of these limitations. Once an animal commands a high market price, as in the case of the tiger, a protected area can provide the ecological framework for survival, but this needs to be backed up by effectively enforced anti-poaching

policies. There is, fortunately, growing expertise in and tools for effective management, monitoring and protection of tigers in conservation areas (WII, 2011). But until CA|TS there was no set of standards and criteria to provide clarity on, or encourage further development and sharing of, best practice management across tiger range countries.

Ensuring effective conservation management

Over the last 20 years several methodologies have been developed and applied for assessing management effectiveness, to enable better understanding of how well conservation areas are being managed and how successfully they ensure conservation objectives are achieved. Many of these assessment systems have been developed to be consistent with the IUCN WCPA Management Effectiveness Framework (Hockings et al, 2006, see Box 1), which has developed guidance on best practice for assessments and has allowed the compilation of results across assessment systems. Around 50 methodologies exist ranging from very simple to more thorough approaches.

The assessment process provides an opportunity for managers and partners to take stock of the effectiveness of conservation areas management. When evaluation is accompanied by the development and implementation of an

action plan based on the findings, more effective management should result. Indeed the time-series data (i.e. recurrent assessment results from the same area) collected by a global study of management effectiveness found that in most cases protected areas show improvements in management with each assessment (Leverington et al, 2010). In part this is because repeat assessments tend to be signs of an agency or project’s long-term commitment to both improve and track area management effectiveness.

Outside protected areas effort has been put into agreeing standards for good management and investigating ways in which standards can be encouraged through certification systems, such as FSC. There are now initiatives under way to bring these two conservation strategies together.

Setting standards for good conservation area management

Assessment and certification systems differ in the extent to which they provide information on success or failure; some give a "score", others a simple pass/fail, while others rely on a more general description of management strengths and weaknesses. The usefulness of assessments, and implementation of results, can often be improved if there is a clear understanding of what managers should be aiming for, by agreeing some basic standards against which to judge an assessment.

The importance of this standard setting has been reinforced by the CBD, which requested the development of standards for protected areas in its Programme of Work on Protected Areas.

As a result of the new emphasis on standards, voluntary assessment and certification schemes based on compliance with management standards have begun to be developed for protected areas. The IUCN Green List (see Box 2) is a major new initiative in this field, for instance.

Vision, Goals, objectives

CA|TS provides an incentive to those responsible for tiger conservation areas to improve the effectiveness of management and so contribute to the goal of doubling the number of tigers by 2022. While this tool focuses on tigers, the CA framework could be applied to other endangered species – particularly those that are highly dependent on conservation in the face of poaching and similar threats.

The mission of CA|TS is to secure safe havens for wild tigers. To do this CA|TS has a:

Vision

• Wild tigers have spaces to live and breed safe from threat resulting in increased populations and recovery of range

• Adoption and implementation of CA|TS Standards ensures tiger habitats are effectively conserved, well-managed and ecologically connected to maintain, secure and recover viable populations.

• CA|TS demonstrates and promotes best practice in protected area management in Asia.

Goals

Objec

tives

• Develop expert-led CA|TS criteria and accreditation processes which are credible and scientifically relevant and linked with associated conservation standards (e.g. IUCN Green List).

• Register the world’s most important tiger areas and develop programmes which mobilise support and capacity for management in order to help these areas meet the CA|TS criteria.

• Establish linkages with global conservation agencies, government agencies /institutions to build capacity and mobilise resources and promote best practices.

• More than 150 tiger conservation areas are registered and well on their way to CA|TS Approved.

• All tiger range countries are actively involved in CA|TS.

• A funding mechanism to support the improvement of registered tiger conservation areas is in place.

Targets by 2022

Why implement CA|TS?

CA|TS aims to provide an incentive for improving the effectiveness of conservation areas as a tool for tiger conservation and to provide a mechanism for monitoring, demonstrating and guaranteeing the effectiveness of the system of tiger conservation areas. CA|TS can provide a range of benefits For a national protected areas system: to help set a baseline and facilitate adaptive management and continual improvement of performance.

The CA|TS Journey

Tigers require large areas of habitat to survive. Their conservation has focused on habitat protection and conservation, through the designation of protected areas, conservation management of forest reserves, designation of wildlife corridors, etc. However, this strategy will only ensure a corresponding and sustainable increase in tiger populations if these areas are effectively, efficiently and equitably managed.

There are three key elements to safeguarding wild tigers. Firstly, protection which is unfortunately an expensive necessity given the scale of the poaching crisis. 100 or more wild tigers are still being lost to poaching annually, although this number is declining.

Secondly, staffing across a range of disciplines but with a focus on protection and professionalization. Nothing beats boots on the ground to reduce the threats to tigers; as an example, a study of 11 protected areas in five Southeast Asian countries from 2005-2019 found some 53,000 snares needed to be removed annually from just this small subset of the tiger range. And lastly, but vitally, sustainable financing. The global deficit in conservation funding is estimated at up to US$300 – 400 billion per year, across the tiger range most of Southeast Asia has insufficient government funding for the task required, posing a major risk to tiger conservation.

With these needs in mind, a handful of conservationists began to explore the ideas behind what became CA|TS in 2011. After two with tiger and conservation experts around the world, CA|TS was launched at the first Asia Parks Congress in 2013. Since then, an enormous amount of time and expertise has gone into developing processes, partnerships and, most importantly, working with sites to ensure good practice management and safe havens for wild tigers.

Since the launch, CA|TS has come a long way with currently 128 sites involved across seven tiger range countries. Some gaps however remain: Myanmar is still in the early development of its tiger conservation action plan and of establishing protected area monitoring, and recent political events have hampered conservation efforts. Thailand and Indonesia have yet to join the programme. The three remaining countries within the tiger range, Cambodia, Lao PDR and Vietnam, no longer have tiger populations. However, the potential for reintroduction has been explored in Cambodia, where CA|TS has been used to assess management conditions.

The CA|TS Partnership

CA|TS was built on the idea of bringing people together who share the same dream to safeguard wild tigers. CA|TS functions through a wide partnership comprising governments, NGOs, donors, experts and academic representatives. National Committees made up of a people from mixed disciplines (e.g., biodiversity and human rights expertise) and from a mix of organisations (e.g., governments and NGOs) run CA|TS in each country or jurisdiction (applicable where the tiger range is only in a small part of a large country as in Russia and China). Independent of this structure, expert reviewers guarantee scientific rigour, and an Executive Committee ensures good governance and equivalence of CA|TS implementation and awarding of Approved status across the tiger range. (Details of the various committee functions can be found in the CA|TS manual).

The CA|TS management team ensures technical and financial viability.

The first global CA|TS meeting was organised in Bangkok, Thailand in 2015, in collaboration with the Thailand Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation, the Global Tiger Forum and WWF-Tigers Alive Initiative. This three-day event with 73 participants from 18 countries addressed two key questions:

1. How can CA|TS improve tiger management in protected areas and other important areas for tigers?

2. How do we encourage and coordinate involvement in CA|TS from government institutions, NGOs and others to sustain and maximise impact?

The highlight of the event saw delegates making a series of pledges and commitments to make CA|TS a reality. Much of our work over the last six years, has focussed on these undertakings and sustaining the enthusiasm and involvement of governments across the tiger range.

In June 2017, a major step forward was the formation of the CA|TS Support Group. The support group now has 13 members (see back cover). Together all those involved, from tiger conservation areas to UN institutions, make up the CA|TS partnership – supporting, developing, advocating and implementing CA|TS to safeguard wild tigers.

Constitution:-

1. CA|TS Council Chair (1)

2. CA|TS Support Group (max 2)

3. GLPCA (Green List) (1)

4. GTF (1)

5. Management team host (1)

6. IUCN WCPA (1)

7. SSC / Tiger Experts (max 3)

8. Protected Area Management Experts (max 2)

9. Capacity building (1)

10. Multilateral agency (max 2)

11. Standards expertise (1)

12. Social Scientist / Communities (1)